The God of the Old Testament was no slumbering slouch, hanging lazily about heaven without deigning to dip a hand into human affairs. This was a Lord who, hand in hand with his favorites among the Jews, performed miracles, bringing them fortune when they obeyed him, and disaster when they failed. Indeed, this system of reward and punishment for faithfulness to the Lord exists as a lingering undercurrent running throughout the Old Testament, as God proves time and again the generosity of his bounty and the power of his wrath in response to the behavior of his chosen people. In fact, He leaves little room for doubt over how the Israelites will be rewarded if they adhere to his will:

“And it shall come to pass, if thou shalt hearken diligently unto the voice of the Lord thy God, to observe and to do all his commandments which I command thee this day, that the Lord thy God will set thee on high above all nations of the earth:

And all these blessings shall come on thee, and overtake thee, if thou shalt hearken unto the voice of the Lord thy God.” (Deuteronomy 28:1-2)

More specifically, no male, female, or cattle among the people will be barren (Deuteronomy 7:14), they will suffer no sickness (Deuteronomy 7:15), and they will consume the peoples delivered unto them (Deuteronomy 7:16). Furthermore, they shall enjoy an international kind of superpower status:

“Thou shalt lend unto many nations, but thou shalt not borrow; and thou shalt reign over many nations, but they shall not reign over thee.” (Deuteronomy 15:6)

In addition, the Lord promises that the people will be blessed in both the city and field, in the fruits of their bodies, their land, their cattle, kine, and sheep, their baskets and stores, when they are coming in and also when they are going out; that they will be given rain and their enemies will be smitten before them. (Deuteronomy 28:3-13)

“Wherefore it shall come to pass, if ye hearken to these judgments, and keep, and do them, that the Lord thy God shall keep unto thee the covenant and the mercy which he sware unto thy fathers.” (Deuteronomy 6:5)

However, as always, there’s a flip side:

“But it shall come to pass, if thou wilt not hearken unto the voice of the Lord thy God, to observe to do all his commandments and his statutes which I command thee this day; that all these curses shall come upon thee, and overtake thee.” (Deuteronomy 28:15)

“The Lord shall set upon thee cursing, vexation, and rebuke, in all that thou settest thine hand unto for to do, until thou be destroyed, and until thou perish quickly; because of the wickedness of thy doings, whereby thou hast forsaken me. (Deuteronomy 28:20)

Failing to adhere to the Lord’s will or to worship Him sufficiently brings down a rain of curses that will make the Israelites envy the plagues the Egyptians endured. Disobedience means you will be cursed in the city and field, in the fruits of your body, land, cattle, kine and sheep, basket and store, and when coming in or when going out. (Deuteronomy 28:16-19) You will receive no rain, be smitten by your enemies, and your carcass shall be meat unto fowl and beasts. On top of which the Lord promises to smite everyone with the botch of Egypt, with emerods, scab, and itch, “whereof thou canst not be healed.” (Deuteronomy 28:27)

But wait, it gets worse. You will also be smitten with madness, blindness, and astonishment of heart. Another man will lay with your betrothed, you won’t get to live in the house you built, or gather grapes from vineyard you planted. Your ox will be slain and your ass taken away, and your sheep will be given to your enemies. You’ll be smitten in the knees and legs, and perhaps even from head to foot, with a sore botch that cannot be healed. Locusts will eat your crops, worms will eat your grapes, and your olive trees shall cast off their fruit. The Lord will bring you to a foreign nation to worship gods of wood and stone, strangers will rise above you, and your enemy from afar will come to destroy you. Your children, however, will fare worst of all, being given over to one’s enemies, taken into captivity, or even eaten in the sieges of enemy nations. (Deuteronomy 28:28-57)

And finally, the Lord will send pestilence, consumption, fever, inflammation, extreme burning, swords, blasting, and mildew (mildew?!), “And they shall pursue thee until thou perish.” Deuteronomy (28:21-22)

“And ye shall be left few in number, whereas ye were as the stars of heaven for multitude, because thou wouldest not obey the voice of the Lord thy God.” (Deuteronomy 28:62)

Seems to me that the punishments far outweigh the blessings, don’t they? But of course, fear of punishment is a vital disciplinary tool. Any kid understands that getting grounded for the weekend for not doing his homework has a much greater effect on his current happiness than maybe, sometime in the distant future, being rewarded for studying hard with a sound financial future.

And at the last God does remind us that it is up to us to choose the life we lead:

“I have set before you life and earth, blessing and cursing: therefore choose life, that both thou and thy seed may live.” (Deuteronomy 30:19)

But even the Old Testament God isn’t a total hard-ass, promising that if you genuinely repent of the sins which brought down his wrath, that He will have compassion and put things back the way they were. (Deuteronomy 30:1-10) Sin and repentance; it frankly foreshadows the New Testament in a way that the judgments of the Old Testament generally do not. Because by the time of the New Testament, of course, it must have been apparent to the Jews that the quality of their condition was not really dependent upon whether they obeyed the Lord or not, just as it is today. How many righteous men are respected and rewarded and how many criminals caught and punished? How many innocents are plagued with disease and death and drought? In modern society it is unbelievably and rather unfortunately obvious that people, whether good or bad, don’t generally get what they deserve; they get what they get. And perhaps this is why the New Testament focuses so much more on the treasures awaiting in heaven than on those which might be enjoyed here on earth. It must have been comforting to the poor and lame and suffering of the ancient world to believe that one day their time, too, would come, as long as they were good, as long as they believed and behaved. As comforting as it is to believe that the wicked who walk among us today in style will one day be cast into a lake of everlasting fire.

Pages

- HOME

- ABOUT

- ON HEARING OF MY MOTHER'S DEATH SIX YEARS AFTER IT HAPPENED

- STORIES FROM MY MEMORY-SHELF

- TO ALL THE PENISES I'VE EVER KNOWN

- THE HANNELACK FANNY, OR HOW I LEARNED TO STOP WORR...

- JUST THE THREE OF US

- MY LIFE WITH MICHAEL: A NOVEL OF SEX, BEER, AND MIDDLE AGE

- WORKS IN PROGRESS

- PUBLICATIONS

- THINGS THAT MAKE ME SMILE

- THE LONG ROAD HOME

Subscribe to my newsletter!

Saturday, January 26, 2013

Saturday, January 19, 2013

The Layperson’s Bible: In Which Paul Signs Some Letters

Good Lord, how I hate this part. I just know I’m going to forget someone and next time I’m in Rome they’re going to give me crap over it. Okay, okay, the most important ones first. “I commend unto you Phebe our sister, which is a servant of the church which is at Cenchrae: That ye receive her in the Lord, as becometh saints, and that ye assist her in whatsoever business she hath need of you.” Hey, that’s pretty good. Maybe she’ll get off my back now about writing her a letter of recommendation. I can’t forget Aquila, but shoot, what’s that other girl’s name? I never remember if it’s Prisca or Priscilla. Priscilla, I think. “Greet Priscilla and Aquila my helpers in Christ Jesus: Who have for my life laid down their own necks: unto whom not only I give thanks, but also all the churches of the Gentiles.” Boy, I really hope it is Priscilla.

And then I’d better greet Epaenetus, the first convert from Achaia – what a stroke that was! – and I ought to thank Mary for all of her hard work, too. What about all the rest? Well, let’s see, I’ll call Amplias my beloved… no, my beloved in the Lord, that sounds more faithful; and then Urbane can be our helper in Christ, and then there are my kinsmen and fellowprisoners Andronicus and Junia; I guess I’d better salute them, too. Geez, this letter’s already twenty pages and the salutations alone are going to be another page at least…how do I even know so many Romans? Better cut to the chase. Let’s just salute Apelles, Aristobulus, Herodion, Narcissus, Tryphena and Tryphosa, Persis, Rufus and his mother, Asyncritus, Phlegon, Herman, Patrobas, Hermes, Philologus, Julia, Nereus and his sister, and don’t forget Olympas. “Salute one another with a holy kiss.” There, that sounds nice. Darn it, I forgot that I promised to say hello on behalf of – well, all those guys. Timotheus, Lucius, Jason, Sosipater. Tertius, Gaius, Erastus, and Quartus salute you. “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all. Amen.”

Here we go, closing out these letters to the Corinthians will be easier – I hardly know any of them personally. I’ll keep it simple; no names this time. “All the brethren greet you. Greet ye one another with an holy kiss.” Oh, I should probably thank them for sending those guys, too. “I am glad of the coming of Stephanus and Fortunatas and Achaicus: for that which was lacking on your part they have supplied.” Wait, does that sound too snarky? Screw it; I’ve already been there twice and Titus once – they should have sent helpers sooner.

I’m not even going to bother saluting those Galatians, who have already strayed from the path. “Brethren, the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit. Amen.” Should I even bother scheduling another trip there? Maybe Tychicus can go after he’s done with the Ephesians and Colossians. Now the Philippians I need to thank for their present. Delicately, though. “Not because I desire a gift: but I desire fruit that may abound to your account… I am full, having received of Epaphroditus the things which were sent from you, an odour of a sweet smell, a sacrifice acceptable, wellpleasing to God."

Boy, it’s getting late. I can make it quick with the Thessalonians and Hebrews – greet the brethren with a kiss, salute the saints, etc. Heck, it’s not as if they’re going to know I’m repeating myself. They’re not going to be sharing my letters, after all, are they?

Still a lot of writing, though. Hey, I’ve got an idea. What if I take this short one to the Colossians and have it do double-duty? “And when this epistle is read among you, cause that it be read also in the church of the Laodiceans.” Ha! No epistle to the Laodiceans; that’ll save some time.

Okay, cool. Finally I can finish off these letters to my sons. The two good ones, anyway. So, let’s invite Titus to spend the winter in Nicopolis with me, and ask him to bring along my lawyer Zenas when he comes; I could really use a consult. Timothy might not be so easily convinced, though; he seems to like wandering around. “Do thy diligence to come shortly unto me.” That’ll get my point across. I hope he takes my hint and brings Mark along; I’m kind of sick of having just Luke around. I’d better remind him to bring my stuff, too; well-intentioned kid, but a bit of a flake sometimes. “The cloke that I left at Troas with Carpus, when thou comest, bring with thee, and the books, but especially the parchments.” No way Carpus gets to keep that cloak another winter, and I’ve used up pretty much all of my parchments on these epistles. Was there something else I was going to ask him about? Oh! I remember; I wanted to warn him about that jerk metalworker. “Alexander the coppersmith did me much evil: the Lord reward him according to his works. Of whom be thou ware also; for he hath greatly withstood our words.” That’ll teach Alexander.

But what on earth am I going to do about Onesimus? That kid is such a… well, let’s just say he’s not the greatest of the Lord’s disciples. Useless is more like it. But what else can I do? He’s got to learn his father’s trade, hasn’t he? I wonder if he’s doing better with the Colossians, but since Tychicus hasn’t written…well, I hope he’s getting the hang of it. Maybe if I just soften his path a bit, they’ll forget about last time. Tug on the ol’ heartstrings, too. He’s my kid, isn’t he? And I’m Paul! “I beseech thee for my son Onesimus, whom I have begotten in my bonds: Which in time past was to thee unprofitable, but now profitable to thee and to me: Whom I have sent again: thou therefore receive him, that is, mine own bowels."

I wonder if he ever paid off those gambling debts. Oh, who am I kidding? And Philemon isn’t one to forget that kind of thing. I mean, I’ve seen his account-books. If it weren’t for that whole prohibition against usury, Onesimus would owe him a fortune by now. Well, I guess there’s nothing else for it. Hard to help the kid from here, but where is he going to go if Philemon turns him away? I’ll just have to accept the responsibility is all. “If he hath wronged thee, or oweth thee ought, put that on mine account; I Paul have written it with mine own hand, I will repay it.” I sure hope that kid grows up soon. Boy, fatherhood’s tough. I almost wish I’d adopted abstinence before I sired that one.

But at least the letters are done. My scribe Tertius thinks they could use revising but I say forget it. They're not literature. It’s not as if they’re going to survive posterity, after all. I mean, future generations surely won’t be reading about my travel plans or my problems with my sons. No one is going to care if I forgot to greet one of the Thessalonian brethren or if I got Priscilla’s name right. Darn it, you know, I think maybe it was Prisca after all…

And then I’d better greet Epaenetus, the first convert from Achaia – what a stroke that was! – and I ought to thank Mary for all of her hard work, too. What about all the rest? Well, let’s see, I’ll call Amplias my beloved… no, my beloved in the Lord, that sounds more faithful; and then Urbane can be our helper in Christ, and then there are my kinsmen and fellowprisoners Andronicus and Junia; I guess I’d better salute them, too. Geez, this letter’s already twenty pages and the salutations alone are going to be another page at least…how do I even know so many Romans? Better cut to the chase. Let’s just salute Apelles, Aristobulus, Herodion, Narcissus, Tryphena and Tryphosa, Persis, Rufus and his mother, Asyncritus, Phlegon, Herman, Patrobas, Hermes, Philologus, Julia, Nereus and his sister, and don’t forget Olympas. “Salute one another with a holy kiss.” There, that sounds nice. Darn it, I forgot that I promised to say hello on behalf of – well, all those guys. Timotheus, Lucius, Jason, Sosipater. Tertius, Gaius, Erastus, and Quartus salute you. “The grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with you all. Amen.”

Here we go, closing out these letters to the Corinthians will be easier – I hardly know any of them personally. I’ll keep it simple; no names this time. “All the brethren greet you. Greet ye one another with an holy kiss.” Oh, I should probably thank them for sending those guys, too. “I am glad of the coming of Stephanus and Fortunatas and Achaicus: for that which was lacking on your part they have supplied.” Wait, does that sound too snarky? Screw it; I’ve already been there twice and Titus once – they should have sent helpers sooner.

I’m not even going to bother saluting those Galatians, who have already strayed from the path. “Brethren, the grace of our Lord Jesus Christ be with your spirit. Amen.” Should I even bother scheduling another trip there? Maybe Tychicus can go after he’s done with the Ephesians and Colossians. Now the Philippians I need to thank for their present. Delicately, though. “Not because I desire a gift: but I desire fruit that may abound to your account… I am full, having received of Epaphroditus the things which were sent from you, an odour of a sweet smell, a sacrifice acceptable, wellpleasing to God."

Boy, it’s getting late. I can make it quick with the Thessalonians and Hebrews – greet the brethren with a kiss, salute the saints, etc. Heck, it’s not as if they’re going to know I’m repeating myself. They’re not going to be sharing my letters, after all, are they?

Still a lot of writing, though. Hey, I’ve got an idea. What if I take this short one to the Colossians and have it do double-duty? “And when this epistle is read among you, cause that it be read also in the church of the Laodiceans.” Ha! No epistle to the Laodiceans; that’ll save some time.

Okay, cool. Finally I can finish off these letters to my sons. The two good ones, anyway. So, let’s invite Titus to spend the winter in Nicopolis with me, and ask him to bring along my lawyer Zenas when he comes; I could really use a consult. Timothy might not be so easily convinced, though; he seems to like wandering around. “Do thy diligence to come shortly unto me.” That’ll get my point across. I hope he takes my hint and brings Mark along; I’m kind of sick of having just Luke around. I’d better remind him to bring my stuff, too; well-intentioned kid, but a bit of a flake sometimes. “The cloke that I left at Troas with Carpus, when thou comest, bring with thee, and the books, but especially the parchments.” No way Carpus gets to keep that cloak another winter, and I’ve used up pretty much all of my parchments on these epistles. Was there something else I was going to ask him about? Oh! I remember; I wanted to warn him about that jerk metalworker. “Alexander the coppersmith did me much evil: the Lord reward him according to his works. Of whom be thou ware also; for he hath greatly withstood our words.” That’ll teach Alexander.

But what on earth am I going to do about Onesimus? That kid is such a… well, let’s just say he’s not the greatest of the Lord’s disciples. Useless is more like it. But what else can I do? He’s got to learn his father’s trade, hasn’t he? I wonder if he’s doing better with the Colossians, but since Tychicus hasn’t written…well, I hope he’s getting the hang of it. Maybe if I just soften his path a bit, they’ll forget about last time. Tug on the ol’ heartstrings, too. He’s my kid, isn’t he? And I’m Paul! “I beseech thee for my son Onesimus, whom I have begotten in my bonds: Which in time past was to thee unprofitable, but now profitable to thee and to me: Whom I have sent again: thou therefore receive him, that is, mine own bowels."

I wonder if he ever paid off those gambling debts. Oh, who am I kidding? And Philemon isn’t one to forget that kind of thing. I mean, I’ve seen his account-books. If it weren’t for that whole prohibition against usury, Onesimus would owe him a fortune by now. Well, I guess there’s nothing else for it. Hard to help the kid from here, but where is he going to go if Philemon turns him away? I’ll just have to accept the responsibility is all. “If he hath wronged thee, or oweth thee ought, put that on mine account; I Paul have written it with mine own hand, I will repay it.” I sure hope that kid grows up soon. Boy, fatherhood’s tough. I almost wish I’d adopted abstinence before I sired that one.

But at least the letters are done. My scribe Tertius thinks they could use revising but I say forget it. They're not literature. It’s not as if they’re going to survive posterity, after all. I mean, future generations surely won’t be reading about my travel plans or my problems with my sons. No one is going to care if I forgot to greet one of the Thessalonian brethren or if I got Priscilla’s name right. Darn it, you know, I think maybe it was Prisca after all…

Saturday, January 12, 2013

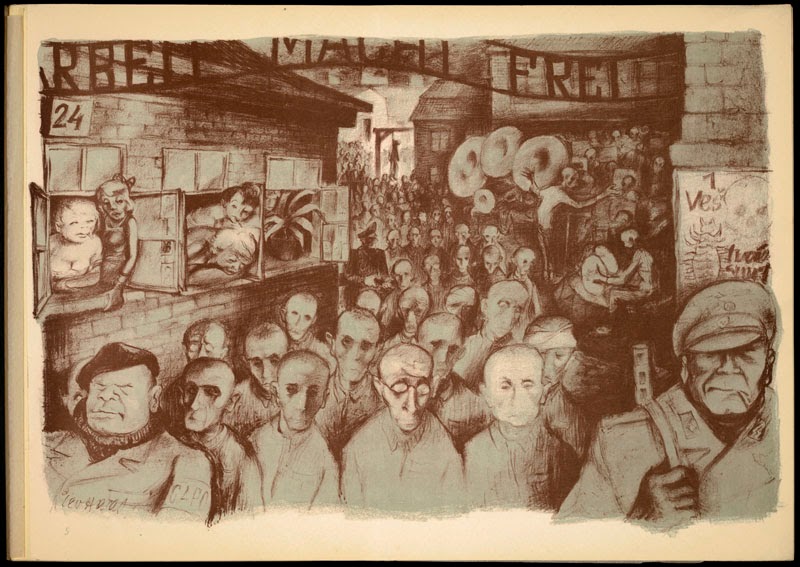

Rudolf Hoess, Commandant of Auschwitz

Hess, Rudolf, Commandant of Auschwitz, tr. Constantine FitzGibbon, World Publishing Company: Cleveland and New York, 1951.

Commandant of Auschwitz combines the autobiography which Rudolf Hoess wrote while awaiting trial at Nuremberg as well as a number of official statements he gave to his interrogators regarding other SS personnel with whom he had significant contact. There is a lot I could say about this book, because Hoess, rather surprisingly, has a number of interesting ideas and observations, particularly in regards to the concept and execution of imprisonment and the lesser-known victims of the concentration-camp system, but for the moment I’ll confine myself to what he has to say about conducting the affairs of Auschwitz.

Hoess makes no bones about his political beliefs; he unwaveringly avers his continued allegiance to the Nazi Party, and, unlike many Nazis, who denied complicity with the concept behind or execution of the Holocaust, even suggests that he would have been in favor of it were it vital to the cause:

“Whether this mass extermination of the Jews was necessary or not was something on which I could not allow myself to form an opinion, for I lacked the necessary breadth of view.” p. 160.

However, what is most fascinating about the book is that as it progresses, it becomes clear that Hoess was, generally speaking, against the customary Nazi treatment of the Jews, not out of compassion for their situation or any sense of wrongdoing in causing their suffering, but for purely bureaucratic reasons.

Thus he complains about the nature of the site, which lacked sufficient water, drainage and building materials for the size it was later to assume; he argues against the massive overcrowding, which caused disease to run rampant and had terrible psychological effects upon the inmates, which he believed led to rapid deterioration in their health; against the incompetence and maliciousness of the guards under his control, whose approach to corporal punishment he felt was detrimental to the objective of maintaining peace in the camp while it conducted its operations. He berates the Food Ministry for constantly reducing rations during the course of the war, not because he had pity for the starving concentration-camp dwellers, no, but because it prevented him from maintaining an adequately-functioning work force. The selection process itself, he argues, was faulty at its core:

“If Auschwitz had followed my constantly repeated advice, and had only selected the most healthy and vigorous Jews, then the camp would have produced a really useful labor force and one that would have lasted.” p. 176.

The implication is that more Jews should have been sent immediately to the gas chambers rather than being corralled into the work details if the goal of attaining adequate war-workers was to be achieved. In other words, if Hoess had had his way, the concentration camps would have contained a large contingent of healthy, well-fed Jews and many more dead ones.

Hoess relates anecdotes of the desperate starvation of the camp residents; of inmates being attacked and beaten by their fellows for a crust of bread, of cannibalism among Russian prisoners-of-war. He assures us that his war-time prisoners became little different from civilian criminals, unhesitant to sacrifice their fellows in order to improve their own condition; in order to get an edge on survival. He speaks of the attachment of the Jews to the members of their own families; of the efforts of the mothers to calm their children as they walked into the gas chambers or to throw them out of the doors, pleading for their young lives, just before they are sealed. And then he tells a story of one Special Detachment Jew who had been assigned to the burning of corpses. When the man pauses for a moment in the course of his labors, Hoess inquires of the Capo in charge as to the cause. The Capo informs him that one of the dead in the pile is the man’s wife.

But following his moment’s pause, the man has already gone back to work. And that is when it struck me, that in spite of the distinction between the powerful and the powerless, what a terrible similarity exists between the Commandant and the prisoner. The Commandant does not deal with people; he deals with issues, problems, supply chains, bureaucracy. He is almost entirely detached from the suffering of those under his care. And likewise the inmate has detached himself from his own suffering; he is unable to acknowledge or permit it to penetrate him. Instead he merely attends to his work, the work that, ironically, makes him free, even as the sign above the gate so illusively promised. Detachment means survival; and the ability to detach oneself from one’s circumstances is perhaps a necessary adaptation. For as long as people are able to view one another without acknowledging their humanity, their personhood, they will treat their fellows cruelly. And in order to endure that cruelty, those who suffer from it will have to become like their oppressors: empty of compassion and feeling, intent only on bare survival.

It is now well-known that many Nazis who were recruited into concentration-camp or extermination services were unable to endure it; indeed, many were transferred, upon request, from participation in the brutalities that accompanied occupation and deportation into other branches of service. Considerable care and effort were expended in making exterminations tolerable for the executioners as well as their victims; as horrendous as the mass gassings were, they were viewed as more humane, less wearing on the soul than the mass shootings which had theretofore been employed. Hoess describes how numerous of his subordinates approached him, expressing deeply-troubled thoughts over the mass exterminations; how he deemed it his duty to appear unmoved. Not all of the Nazis were able to view their captives as chattel, as mere bodies to be fed and housed and employed and killed and burned, any more than some of their victims were able to forget the essential humanity of their captors. Consider Hoess’ description of the Allied air raids, which brought terror to the skies over Germany and the occupied lands:

“Attacks of unprecedented fury were made on factories where prisoners were employed. I saw how the prisoners behaved, how guards and prisoners cowered together and died together in the same improvised shelters, and how the prisoners helped the wounded guards.

During such heavy raids, all else was forgotten. They were no longer guards or prisoners, but only human beings trying to escape from the hail of bombs.” p. 183.

Humans, one and all. Hoess is not one of the Nazis who viewed the Jews as somehow less than human, and therefore worthy of extinction. He sincerely believes that they were a threat to what he sees as the truly German way of life, and that the measures that were taken against them were necessary in order to preserve the integrity of the nation. He is therefore offended by the vicious propaganda propagated by publications such as Der Stürmer, believing its exaggerated attacks upon Jewish morals and behavior capable of backfiring and creating sympathy for the Jews. He argues that the nations conquered by Germany during the Second World War should have been treated with greater respect and kindness, which would have unmanned much of the resistance which grew following the invasion. And finally, in the ultimate expression of utter disregard for the unadulterated evil imposed upon the unoffending peoples of the world, Hoess at last concedes that the Holocaust should not have occurred. But listen to his reasons why:

“I also see now that the extermination of the Jews was fundamentally wrong. Precisely because of these mass exterminations, Germany has drawn upon herself the hatred of the entire world. It in no way served the cause of anti-Semitism, but on the contrary brought the Jews far closer to their ultimate objective.” p. 198.

The Holocaust was wrong, according to Hoess, not owing to fundamental human principles of kindness and decency, or compassion for one’s fellows, but because it did not serve the Nazi cause. Which eerily implies that he believes that it would have been “right” had it only served the purpose for which it was intended. Is that, too, an essentially human characteristic? To be able to justify the means, if they achieve what is perceived to be a desirable end?

Commandant of Auschwitz combines the autobiography which Rudolf Hoess wrote while awaiting trial at Nuremberg as well as a number of official statements he gave to his interrogators regarding other SS personnel with whom he had significant contact. There is a lot I could say about this book, because Hoess, rather surprisingly, has a number of interesting ideas and observations, particularly in regards to the concept and execution of imprisonment and the lesser-known victims of the concentration-camp system, but for the moment I’ll confine myself to what he has to say about conducting the affairs of Auschwitz.

Hoess makes no bones about his political beliefs; he unwaveringly avers his continued allegiance to the Nazi Party, and, unlike many Nazis, who denied complicity with the concept behind or execution of the Holocaust, even suggests that he would have been in favor of it were it vital to the cause:

“Whether this mass extermination of the Jews was necessary or not was something on which I could not allow myself to form an opinion, for I lacked the necessary breadth of view.” p. 160.

However, what is most fascinating about the book is that as it progresses, it becomes clear that Hoess was, generally speaking, against the customary Nazi treatment of the Jews, not out of compassion for their situation or any sense of wrongdoing in causing their suffering, but for purely bureaucratic reasons.

Thus he complains about the nature of the site, which lacked sufficient water, drainage and building materials for the size it was later to assume; he argues against the massive overcrowding, which caused disease to run rampant and had terrible psychological effects upon the inmates, which he believed led to rapid deterioration in their health; against the incompetence and maliciousness of the guards under his control, whose approach to corporal punishment he felt was detrimental to the objective of maintaining peace in the camp while it conducted its operations. He berates the Food Ministry for constantly reducing rations during the course of the war, not because he had pity for the starving concentration-camp dwellers, no, but because it prevented him from maintaining an adequately-functioning work force. The selection process itself, he argues, was faulty at its core:

“If Auschwitz had followed my constantly repeated advice, and had only selected the most healthy and vigorous Jews, then the camp would have produced a really useful labor force and one that would have lasted.” p. 176.

The implication is that more Jews should have been sent immediately to the gas chambers rather than being corralled into the work details if the goal of attaining adequate war-workers was to be achieved. In other words, if Hoess had had his way, the concentration camps would have contained a large contingent of healthy, well-fed Jews and many more dead ones.

Hoess relates anecdotes of the desperate starvation of the camp residents; of inmates being attacked and beaten by their fellows for a crust of bread, of cannibalism among Russian prisoners-of-war. He assures us that his war-time prisoners became little different from civilian criminals, unhesitant to sacrifice their fellows in order to improve their own condition; in order to get an edge on survival. He speaks of the attachment of the Jews to the members of their own families; of the efforts of the mothers to calm their children as they walked into the gas chambers or to throw them out of the doors, pleading for their young lives, just before they are sealed. And then he tells a story of one Special Detachment Jew who had been assigned to the burning of corpses. When the man pauses for a moment in the course of his labors, Hoess inquires of the Capo in charge as to the cause. The Capo informs him that one of the dead in the pile is the man’s wife.

But following his moment’s pause, the man has already gone back to work. And that is when it struck me, that in spite of the distinction between the powerful and the powerless, what a terrible similarity exists between the Commandant and the prisoner. The Commandant does not deal with people; he deals with issues, problems, supply chains, bureaucracy. He is almost entirely detached from the suffering of those under his care. And likewise the inmate has detached himself from his own suffering; he is unable to acknowledge or permit it to penetrate him. Instead he merely attends to his work, the work that, ironically, makes him free, even as the sign above the gate so illusively promised. Detachment means survival; and the ability to detach oneself from one’s circumstances is perhaps a necessary adaptation. For as long as people are able to view one another without acknowledging their humanity, their personhood, they will treat their fellows cruelly. And in order to endure that cruelty, those who suffer from it will have to become like their oppressors: empty of compassion and feeling, intent only on bare survival.

It is now well-known that many Nazis who were recruited into concentration-camp or extermination services were unable to endure it; indeed, many were transferred, upon request, from participation in the brutalities that accompanied occupation and deportation into other branches of service. Considerable care and effort were expended in making exterminations tolerable for the executioners as well as their victims; as horrendous as the mass gassings were, they were viewed as more humane, less wearing on the soul than the mass shootings which had theretofore been employed. Hoess describes how numerous of his subordinates approached him, expressing deeply-troubled thoughts over the mass exterminations; how he deemed it his duty to appear unmoved. Not all of the Nazis were able to view their captives as chattel, as mere bodies to be fed and housed and employed and killed and burned, any more than some of their victims were able to forget the essential humanity of their captors. Consider Hoess’ description of the Allied air raids, which brought terror to the skies over Germany and the occupied lands:

“Attacks of unprecedented fury were made on factories where prisoners were employed. I saw how the prisoners behaved, how guards and prisoners cowered together and died together in the same improvised shelters, and how the prisoners helped the wounded guards.

During such heavy raids, all else was forgotten. They were no longer guards or prisoners, but only human beings trying to escape from the hail of bombs.” p. 183.

Humans, one and all. Hoess is not one of the Nazis who viewed the Jews as somehow less than human, and therefore worthy of extinction. He sincerely believes that they were a threat to what he sees as the truly German way of life, and that the measures that were taken against them were necessary in order to preserve the integrity of the nation. He is therefore offended by the vicious propaganda propagated by publications such as Der Stürmer, believing its exaggerated attacks upon Jewish morals and behavior capable of backfiring and creating sympathy for the Jews. He argues that the nations conquered by Germany during the Second World War should have been treated with greater respect and kindness, which would have unmanned much of the resistance which grew following the invasion. And finally, in the ultimate expression of utter disregard for the unadulterated evil imposed upon the unoffending peoples of the world, Hoess at last concedes that the Holocaust should not have occurred. But listen to his reasons why:

“I also see now that the extermination of the Jews was fundamentally wrong. Precisely because of these mass exterminations, Germany has drawn upon herself the hatred of the entire world. It in no way served the cause of anti-Semitism, but on the contrary brought the Jews far closer to their ultimate objective.” p. 198.

The Holocaust was wrong, according to Hoess, not owing to fundamental human principles of kindness and decency, or compassion for one’s fellows, but because it did not serve the Nazi cause. Which eerily implies that he believes that it would have been “right” had it only served the purpose for which it was intended. Is that, too, an essentially human characteristic? To be able to justify the means, if they achieve what is perceived to be a desirable end?

|

| Lithograph by Leo Haas (1901-1983), Holocaust artist, who survived Theresienstadt and Auschwitz. From the Center for Jewish History - no known copyright restrictions. |

Saturday, January 5, 2013

The Layperson’s Bible: Sexual Behavior Part III - Adultery

It’s obvious that in the Biblical world, adultery was a big no-no; it even made it into the top ten commandments, twice if you count both the prohibition itself and the admonishment not to covet thy neighbor’s wife. Logically, this is actually somewhat surprising, because marriage in the Bible seems to be a pretty simple affair. Consider, for example, the story of Jacob (Genesis 29, 30), who is given to wife both Leah and her sister Rachel, which may be the source of the later prohibition against marrying sisters, for it led to considerable drama. When Rachel stops conceiving, she gives Jacob her maid to wife so that she may “bear upon her knees,” and then when Leah stops conceiving, she gives Jacob her maid to wife, too. All with little more fanfare than:

“And she gave him…her handmaid to wife; and Jacob went in unto her.” (Genesis 30:4)

In other words, “take a wife” often seems to be merely a euphemistic way of saying “had sex with,” except that said intercourse tended to create a permanent bond between the parties involved. That is, sex was what joined two people in marriage. This concept, of course, has carried down to the present day, as failure to consummate is still considered acceptable grounds for annulment. However, the very lack of formality involved in entering into wedlock might be viewed as actually encouraging future adultery, because it’s much more difficult not to stray when you acquire your lifelong mate through a single dalliance.

Unless, of course, you were a man, in which case, subject to certain stipulations, you were encouraged to have multiple wives and/or concubines, the possession of which was not deemed unfaithfulness to either your original or any of your subsequent spouses. A man was therefore not generally considered adulterous unless he engaged in sexual relations with another man’s wife or betrothed, for which he could be punished as severely as the straying woman:

“Moreover thou shalt not lie carnally with thy neighbor’s wife, to defile thyself with her.” (Leviticus 18:20)

“If a man be found lying with a woman married to an husband, then they shall both of them die.” (Deuteronomy 22:22)

“If a damsel that is a virgin be betrothed unto an husband, and a man find her in the city, and lie with her;

Then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of the city, and ye shall stone them with stones until they die: the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city; and the man, because he hath humbled his neighbor’s wife.” (Deuteronomy 22:23-24)

Notice, however, that the woman and man are punished for entirely different reasons: the woman for being unfaithful to her husband or fiancé, and the man for sleeping with a woman who belongs to another. In other words, you can take as many wives as you want, as long as you don’t take someone else’s.

Interestingly, though, the rape of an unwilling woman is still considered a capital offence:

“But if a man find a betrothed damsel in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then the man only that lay with her shall die:

But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing; there is in the damsel no sin worthy of death: for as when a man riseth against his neighbour, and slayeth him, even so is this matter:

For her found her in the field, and the betrothed damsel cried, and there was none to save her.” (Deuteronomy 22:25-27)

This latter scenario offers a presumption of innocence which contrasts sharply with the situation in which the pair are caught in the city. If they were in the city it is assumed that she must not have cried, or someone would have heard her; and if in the country that she would surely have cried although there was no one there to hear. The smart woman, therefore, would always be certain to conduct her affairs in the country.

If the faithfulness of a woman was suspect, various methods could be employed for proving her virtue or lack thereof. For example, if a husband had reason to believe that his wife was fooling around, he could have her subjected to the bitter-water test:

“And when [the priest] hath made her to drink the water, then it shall come to pass, that, if she be defiled, and have done trespass against her husband, that the water that causeth the curse shall enter into her, and become bitter, and her belly shall swell, and her thigh shall rot: and the woman shall be a curse among her people.” (Numbers 5:26)

Now I have no idea what kind of poison they were feeding these women suspected of adultery, or how many of them were deformed or even killed thereby, but it does remind me an awful lot of that test they used to perform on suspected witches, of throwing them into the water and then sanctifying those who sank and burning those who swam.

In the Gospels, Jesus also has some interesting things to say about adultery, most famous of which is probably:

“Whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart.” (Matthew 5:28)

Remarks of this nature distinctly convey the Christian conception of sin existing in thought as well as in deed, which makes it much more difficult to avoid. However, Jesus is also quite adamant on the permanence and sanctity of marriage; indeed, his teachings may have been almost solely responsible for Christian prohibitions against divorce. In fact, one would be safe in arguing that “until death do us part” is an entirely New Testament concept, which certainly did not apply in the time of Moses, and which ultimately led Jesus’ disciples to a very modern-day conclusion:

“The Pharisees also came unto [Jesus], tempting him, and saying unto him, Is it lawful for a man to put away his wife for every cause?

And he answered and said unto them, Have ye not read, that he which made them at the beginning made them male and female,

And said, For this cause shall a man leave father and mother, and shall cleave to his wife: and they twain shall be one flesh?

Wherefore they are no more twain, but one flesh. What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder.

They say unto him, Why did Moses then command to give a writing of divorcement, and to put her away?

He saith unto them, Moses because of the hardness of your hearts suffered you to put away your wives: but from the beginning it was not so.

And I say unto you, Whosoever shall put away his wife, except it be for fornication, and shall marry another, committeth adultery: and whoso marrieth her which is put away doth commit adultery.

His disciples say unto him, If the case of the man be so with his wife, it is not good to marry.” (Matthew 19:3-10)

“And she gave him…her handmaid to wife; and Jacob went in unto her.” (Genesis 30:4)

In other words, “take a wife” often seems to be merely a euphemistic way of saying “had sex with,” except that said intercourse tended to create a permanent bond between the parties involved. That is, sex was what joined two people in marriage. This concept, of course, has carried down to the present day, as failure to consummate is still considered acceptable grounds for annulment. However, the very lack of formality involved in entering into wedlock might be viewed as actually encouraging future adultery, because it’s much more difficult not to stray when you acquire your lifelong mate through a single dalliance.

Unless, of course, you were a man, in which case, subject to certain stipulations, you were encouraged to have multiple wives and/or concubines, the possession of which was not deemed unfaithfulness to either your original or any of your subsequent spouses. A man was therefore not generally considered adulterous unless he engaged in sexual relations with another man’s wife or betrothed, for which he could be punished as severely as the straying woman:

“Moreover thou shalt not lie carnally with thy neighbor’s wife, to defile thyself with her.” (Leviticus 18:20)

“If a man be found lying with a woman married to an husband, then they shall both of them die.” (Deuteronomy 22:22)

“If a damsel that is a virgin be betrothed unto an husband, and a man find her in the city, and lie with her;

Then ye shall bring them both out unto the gate of the city, and ye shall stone them with stones until they die: the damsel, because she cried not, being in the city; and the man, because he hath humbled his neighbor’s wife.” (Deuteronomy 22:23-24)

Notice, however, that the woman and man are punished for entirely different reasons: the woman for being unfaithful to her husband or fiancé, and the man for sleeping with a woman who belongs to another. In other words, you can take as many wives as you want, as long as you don’t take someone else’s.

Interestingly, though, the rape of an unwilling woman is still considered a capital offence:

“But if a man find a betrothed damsel in the field, and the man force her, and lie with her: then the man only that lay with her shall die:

But unto the damsel thou shalt do nothing; there is in the damsel no sin worthy of death: for as when a man riseth against his neighbour, and slayeth him, even so is this matter:

For her found her in the field, and the betrothed damsel cried, and there was none to save her.” (Deuteronomy 22:25-27)

This latter scenario offers a presumption of innocence which contrasts sharply with the situation in which the pair are caught in the city. If they were in the city it is assumed that she must not have cried, or someone would have heard her; and if in the country that she would surely have cried although there was no one there to hear. The smart woman, therefore, would always be certain to conduct her affairs in the country.

If the faithfulness of a woman was suspect, various methods could be employed for proving her virtue or lack thereof. For example, if a husband had reason to believe that his wife was fooling around, he could have her subjected to the bitter-water test:

“And when [the priest] hath made her to drink the water, then it shall come to pass, that, if she be defiled, and have done trespass against her husband, that the water that causeth the curse shall enter into her, and become bitter, and her belly shall swell, and her thigh shall rot: and the woman shall be a curse among her people.” (Numbers 5:26)

Now I have no idea what kind of poison they were feeding these women suspected of adultery, or how many of them were deformed or even killed thereby, but it does remind me an awful lot of that test they used to perform on suspected witches, of throwing them into the water and then sanctifying those who sank and burning those who swam.

In the Gospels, Jesus also has some interesting things to say about adultery, most famous of which is probably:

“Whosoever looketh on a woman to lust after her hath committed adultery with her already in his heart.” (Matthew 5:28)

Remarks of this nature distinctly convey the Christian conception of sin existing in thought as well as in deed, which makes it much more difficult to avoid. However, Jesus is also quite adamant on the permanence and sanctity of marriage; indeed, his teachings may have been almost solely responsible for Christian prohibitions against divorce. In fact, one would be safe in arguing that “until death do us part” is an entirely New Testament concept, which certainly did not apply in the time of Moses, and which ultimately led Jesus’ disciples to a very modern-day conclusion:

“The Pharisees also came unto [Jesus], tempting him, and saying unto him, Is it lawful for a man to put away his wife for every cause?

And he answered and said unto them, Have ye not read, that he which made them at the beginning made them male and female,

And said, For this cause shall a man leave father and mother, and shall cleave to his wife: and they twain shall be one flesh?

Wherefore they are no more twain, but one flesh. What therefore God hath joined together, let not man put asunder.

They say unto him, Why did Moses then command to give a writing of divorcement, and to put her away?

He saith unto them, Moses because of the hardness of your hearts suffered you to put away your wives: but from the beginning it was not so.

And I say unto you, Whosoever shall put away his wife, except it be for fornication, and shall marry another, committeth adultery: and whoso marrieth her which is put away doth commit adultery.

His disciples say unto him, If the case of the man be so with his wife, it is not good to marry.” (Matthew 19:3-10)

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)